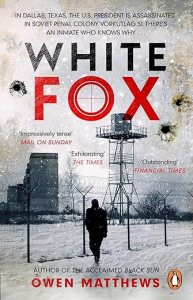

I read White Fox by Matthew Owen, a Cold War thriller, with great pleasure.

The year is 1963. Alexander Vasin, a disgraced KGB officer, has been exiled to the worst posting imaginable: head of a remote Siberian gulag where the Soviet regime sends its own fallen intelligence officers to disappear quietly. When a prisoner revolt erupts, Vasin finds himself fleeing across the frozen wastelands with a mysterious prisoner who may hold the most dangerous secret of the Cold War era, the truth about who really ordered J.F. Kennedy’s assassination.

What follows is a relentless cat-and-mouse chase from the desolate gulags of Siberia to the grey, oppressive neighbourhoods of St Petersburg, with the full machinery of the KGB hunting them both.

Owen has crafted a page-turner that doesn’t sacrifice character for plot or atmosphere for pace. The tension builds beautifully, with expertly timed rises and falls that kept me constantly focused. Just when I thought Vasin has found a moment of safety, Owen pulled the rug out. Just when the net seemed to be closing inescapably, a desperate gambit opened a sliver of possibility.

This isn’t the relentless, exhausting assault of some modern thrillers that mistake constant action for tension. Owen crafts his story’s suspense from letting readers catch their breath just long enough to wonder what comes next.

The real triumph of White Fox is its characters. Alexander Vasin feels utterly authentic, a man caught between his conditioning as a Soviet officer, his survival instincts, and a gradually awakening moral compass. He’s neither hero nor villain, but something far more interesting: a product of his system trying to navigate impossible choices.

The supporting cast is equally well-drawn. Even minor characters who appear briefly feel like real people with histories, motivations, and inner lives. This is crucial in a thriller set in the Soviet system, where paranoia, loyalty, and betrayal form an impossibly tangled web. You can never quite be sure who will help, who will betray, and who will surprise you entirely. I especially enjoyed the description of the street kid gang in St Petersburg\

Owen resists the temptation to make his Soviet characters into cartoonish villains or his protagonist into a secret Western sympathizer. These are people operating within the logic of their world, which makes their choices feel genuine and their conflicts deeply human.

Owen’s writing captures the bleak and sometimes hopeless atmosphere of Soviet Russia with remarkable precision. The frozen Siberian wasteland feels genuinely hostile; not just cold, but a place designed to break a human spirit. The grey Soviet streets convey that distinctive combination of monumentalism and shabbiness, grandeur and decay.

But it’s the smaller details that really sell the setting: the ritual of drinking in a communal apartment, the careful dance of conversation in a bugged room, the way people measure risk in every interaction. Owen clearly understands the texture of life in the Soviet system, where everyone is simultaneously watcher and watched.

The inclusion of the JFK assassination as a plot element could easily have felt gimmicky, but Owen handles it deftly. Rather than trying to “solve” the assassination or present a definitive alternate history, he uses it to raise the stakes to world-historical levels while keeping the focus squarely on his characters’ personal struggles. (And he explains it in more detail in the Author’s Notes at the end of the book – most interesting!)

The question isn’t really whether there was Soviet involvement in Kennedy’s death; the question is what Vasin will do with dangerous knowledge, what loyalty means when your country has betrayed you, and whether truth matters more than survival.

I should confess something embarrassing: I only realized after finishing White Fox that it’s Book 3 in Owen’s trilogy. I’d previously read and thoroughly enjoyed Black Sun (Book 1), loved it, and have Book 2 (Red Traitor) sitting on my shelf. Somehow, I managed to read the series out of order, but I think it doesn’t matter other than to explain how Vasin had been transferred from Moscow to Siberia.) In fact, White Fox works perfectly as a standalone thriller. Owen provides enough context that I never felt lost, and the story is complete in itself. That said, now I’m even more eager to read Red Traitor to see how Vasin’s journey developed between the two books I’ve experienced. And really, who’s never eaten dessert in the middle a meal? So read a trilogy out of order – it’s called ‘living on the edge’ in reader form 🙂

White Fox is a superb thriller that respects its readers’ intelligence while delivering genuine page-turning suspense. Owen has created a protagonist worth following through multiple books, a setting rendered with atmospheric precision, and a plot that maintains tension without sacrificing plausibility.